A multiple-day hiking trip does not start with simply strapping on your boots and starting to walk. Such a trip usually requires careful planning, starting with determining your destination, and how you are going to get there. The same goes for a successful thesis project. In this post, I will discuss how you can write a great research proposal.

If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail – Benjamin Franklin

The purpose of a research proposal

Before you start working on your thesis, it is crucial to have a clear destination (or, goal): what is it that you want to achieve? What question do you want to answer? You also need to determine how you are going to get there (or, what approach you will take to achieve your goal). Without a clear definition of these elements, it will be like hiking without a map. This is why you should write a clear research proposal. The proposal will define the goal of your research project, and describe how you are going to get there. And if you ever get lost along the way, the proposal can help you find your way back. The proposal also offers the opportunity for others (fellow students, teachers, etc.) to give feedback, so you can make improvements to your plan.

Elements of a good research proposal

There are many ways in which you can write a proposal, but there are four important elements that every research proposal needs to have.

- Knowledge gap

- Objective(s) and (optionally) research questions

- Materials and methods

- Time schedule

Knowledge gap

The term knowledge gap probably doesn’t need a lot of explanation. With the knowledge gap, the researcher (you) shows what is still unknown. It’s usually given towards the end of the introduction, and the content of the introduction should support the knowledge gap by (1) setting the scene and delineating the workfield, (2) identifying a problem, and (3) what research has been done to solve this problem. Naturally, this sequence of information leads to what has not been studied; the knowledge gap. Many students forget to explicitly include the knowledge gap in their proposal, because it can seem so obvious. Keep in mind, however, that you have to take the reader by the hand, and that you should never assume that the reader will automatically understand what you mean. It’s better to be a little bit repetitive than to be unclear.

Objective(s) and research questions

The objective is one of the most important elements of a good research proposal. It can therefore be wise to spend some time on formulating your objective clearly. Writing a good objective can be tricky, but practice makes perfect. Discuss this with your supervisor, or (maybe even better) someone that is not directly involved in your project.

- Specific – The action should be well-defined and unambiguous.

- Measurable – It should be easy to determine the outcome, so the objective should be clearly linked to a result.

- Achievable – The objective should not be too difficult given the resources and skills you have.

- Relevant – If the objective is achieved, it should (partly) fill the knowledge gap you identified earlier.

- Timebound – The objective should be achievable within the time that you are given for the project.

A well defined objective is clear, concise, and actionable. You should make sure that the reader understands your objective, and what the expected results are. Make it clear to the reader where the objective is stated, by simply mentioning it explicitly in your text. For example, use a phrase like “The objective of this study is…”, or “The aim of this research is to…”.

When you start formulating your objective, start by thinking about what your most important result will be. For example, if you plan to show the estimated effect of food supplements on weight gain, your objective could be:

The objective of this study is to estimate the effect of using food supplements on weight gain from observational data.

This objective clearly states what you will do (estimate), and what the result will be (an estimate of the effect). This may seem obvious, but many students would write something like:

The objective of this study is to find a relationship between food supplements and weight gain from observational data.

This objective uses a very vague action (find), and it is not directly clear what the result will look like (there are many ways to show a relationship, and what does a “relationship” even mean in this context?).

Materials and methods

Keep this short and simple. There is no need to mention all the details right now. Just make sure that your reader can understand what your approach will be in very general terms.

Time schedule

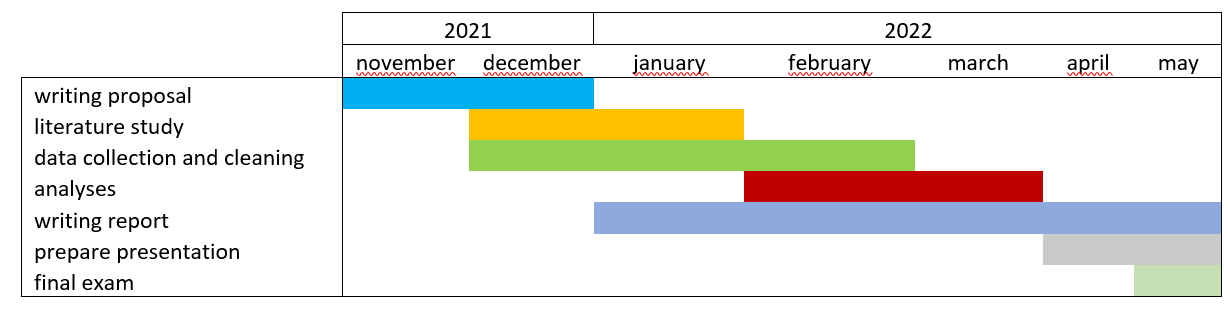

Finally, the time schedule. For each of the tasks in your project, try to estimate how much time it will take you. A useful format to present this kind of information is a Gantt chart, where tasks are presented in rows, and time is presented in columns. An example of a Gantt chart is shown below. Ask for feedback on your time schedule, especially from people who have worked on similar projects before. This ensures that your proposed time schedule is realistic.

Plan B

Once your proposal is finished, you’re ready to get started! But then, life happens: your experiment fails, the data that was promised is not delivered, or a global pandemic makes it impossible for you to travel to Australia where you were supposed to study the effects of sunscreen on coral reefs. Don’t worry, these things happen all the time. Unexpected events are a part of life and of doing research. Nothing ever goes exactly according to plan.

It is important to remember that your proposal is not carved in stone. It is perfectly fine to adjust your plans along the way. For example, if your experiment fails, you could consider to use data from an earlier experiment, or write your thesis about what went wrong during the experiment so others can learn from your mistakes.

How long should your research proposal be?

As with any written scientific text, the length of the text itself is not very relevant. In general, a text should effectively and efficiently serve its purpose (i.e. communicating a message). This can sometimes takes 5 pages, and sometimes only takes 1 page. However, if we compare two texts of different lengths that contain exactly the same information, the shorter text is usually better. Using to many words for a simple message can make your text difficult and frustrating to read. So, just make sure that all important elements of your proposal are clearly communicated to the reader, while trying to be concise.

Of course, you should always comply to the word or page limit if there is one. In those cases, try to communicate your message as efficiently as possible. Sometimes, you are even confronted with a minimum number of words or pages you have to use. Personally, I think such a requirement doesn’t help anyone. If you can convey the same message with less words, then the shorter text is the better one. Adding words simply because someone told you to can only make your text slow to read and difficult to understand. Try to get some feedback on the clarity of your proposal, and add information on things that are unclear.